Sitar, Space, and Ustad Shahid Parvez

How a great sitar player rescued me from postmodernism, only to show me that I was on the right track.

When it comes to sitar music, Ustad Shahid Parvez is the one I go to first.

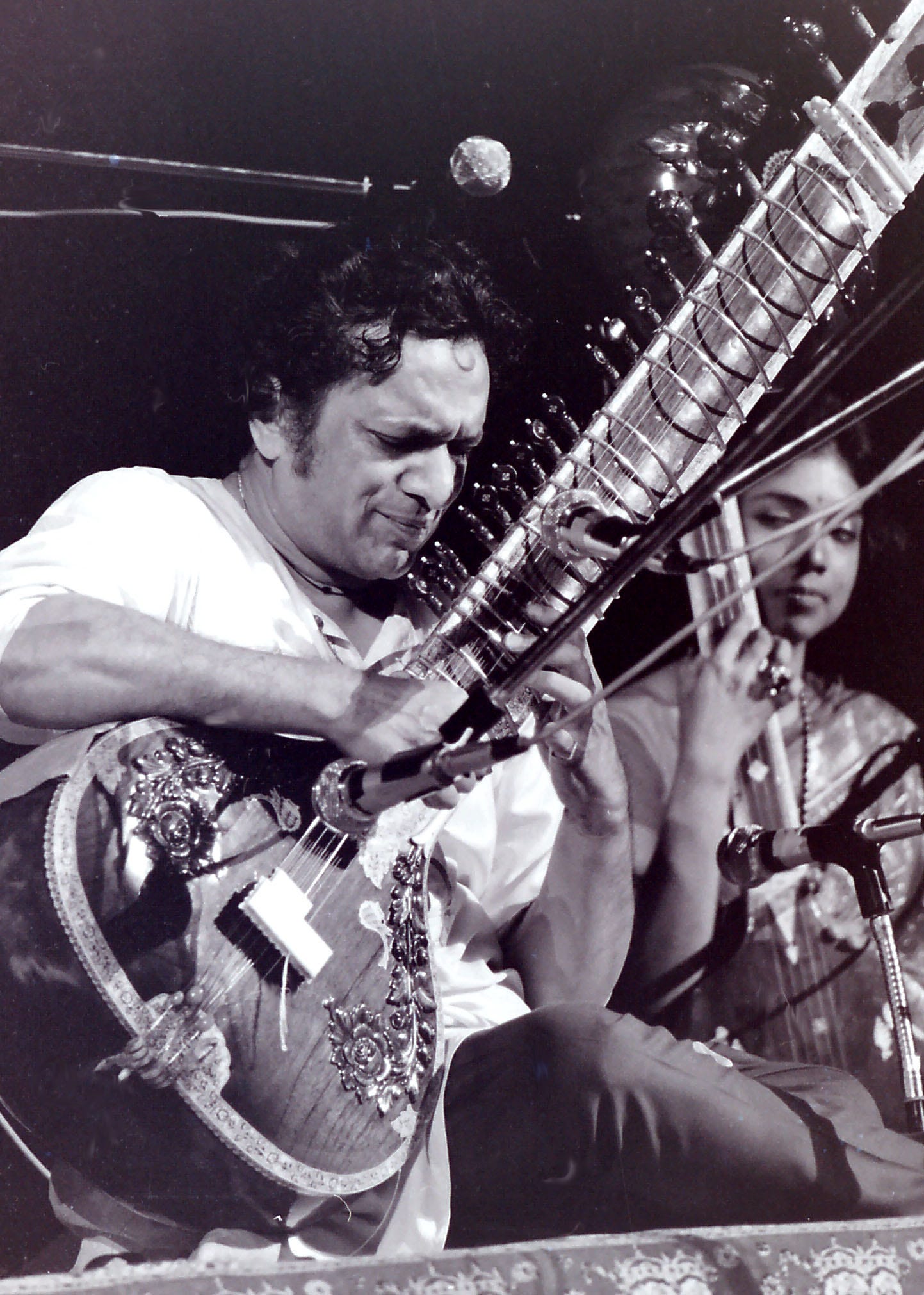

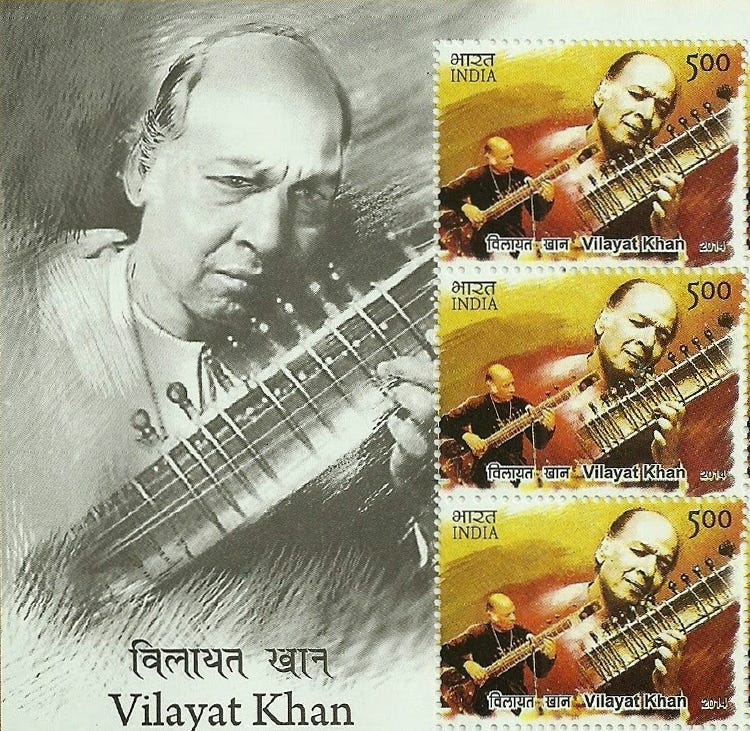

I’ve been listening to him consistently for twenty-five years. Not all the time, certainly not as a student, and not to the exclusion of Pandit Ravi Shankar and Ustad Vilayat Khan, the two sitar players widely held as the greatest of the last century.

Parvez holds a special place for me because of the ways he approaches space in his music. You hear it when he’s performing the opening alaap to any piece. He’ll hold a note, bend the string, and bring out three or four more notes to complete the melody within the same fret. In moments like this, my ears connect with my mind’s eye, visualizing the scene in different ways. Parvez is holding a pen, marking a point, and drawing what might be a single line in a Jackson Pollock painting. It also feels like his note has become a shooting star, flying through the points of a constellation before dissolving into outer space.

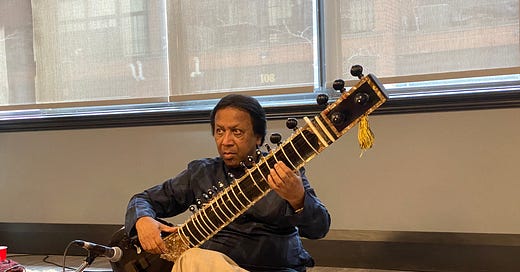

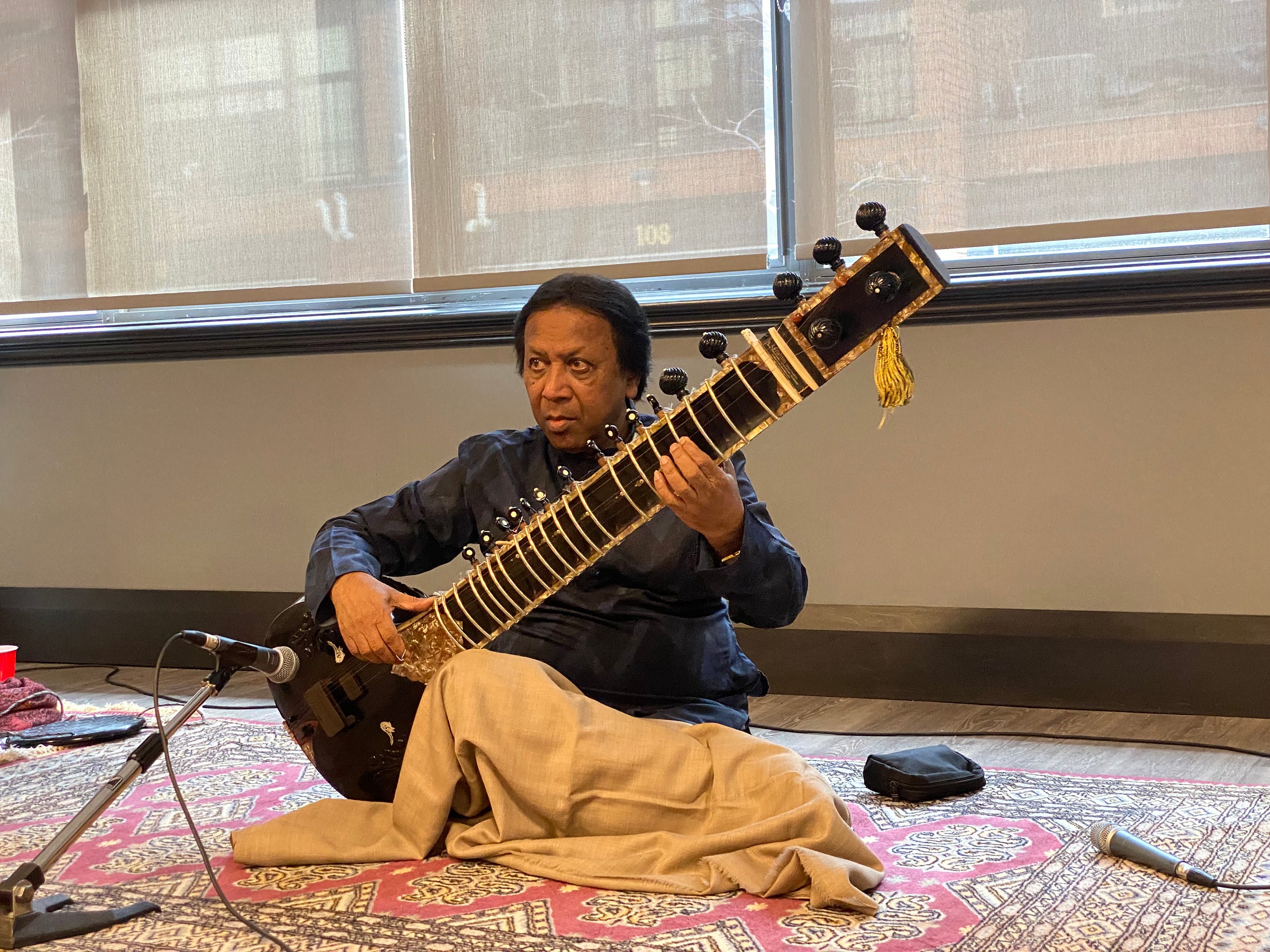

The last seconds of this video I recorded from a recent performance in Toronto almost captures the technique I’m describing. Headphones are recommended.

When I first heard Parvez perform in the early 2000s at Raga-Mala concerts in Toronto, I was also entering my doctoral studies and deeply immersed in what all of us in academia called “theory.” This was also a time for the last hurrahs of postmodernism in philosophy, literature, and art, and across these fields, I noticed a rhetorical emphasis on the importance of space. Space came up in Michel Foucault’s heterotopias, Homi Bhabha’s “spaces of time”, and Anish Kapoor’s bright red and metallic voids.

From this perspective, Parvez’s music sounded like it was part of the same continuum, a possible exemplar of postmodern classical Hindustani music, which is how I began describing Parvez to anyone looking for alternatives to the Ravi-Vilayat generation or to non-Western forms of contemporary art music.

Of course, I was wrong and for so many reasons too, the main one being that “postmodern” is not how Parvez describes his own music. Now, I’m not saying that he or any artist is the critical authority on their work and that critics must align their descriptions with the artist’s self-perception. Rather, it’s about being humble with our intellectual freedom. The postcolonialist in me also remembers that one must always be mindful about elevating non-Western culture with the rhetorical tools of the West, even when the rhetoric aims to have countercultural effects on the West – as was the case with postmodernism. It’s not that these tools don’t work. My point is about being careful.

Postmodern or not, the thing is that I really believed (and still believe) that Parvez’s music deserved to be elevated because of his unique approach to the sitar. I’ve shared this feeling with other more technically knowledgeable fans of classical Hindustani music too. They all agreed that Parvez is a contemporary master of the instrument. I still remember how a disciple introduced one of Parvez’s concerts in Toronto with sentiments from Ravi Shankar and Vilayat Khan: “with Shahid Parvez, the sitar has a future.”

However, my fellow rasikas also insisted that what I was hearing in Parvez’ sitar was a gayaki style, where the instrumentalist’s goal is to achieve the same expressive qualities that are characteristic to the voice, the most culturally elevated form of Hindustani music. One of them added that Parvez is also playing in the style of his guru, which is also to say that Parvez is essentially playing traditional music (and therefore not modern, let alone postmodern, music).

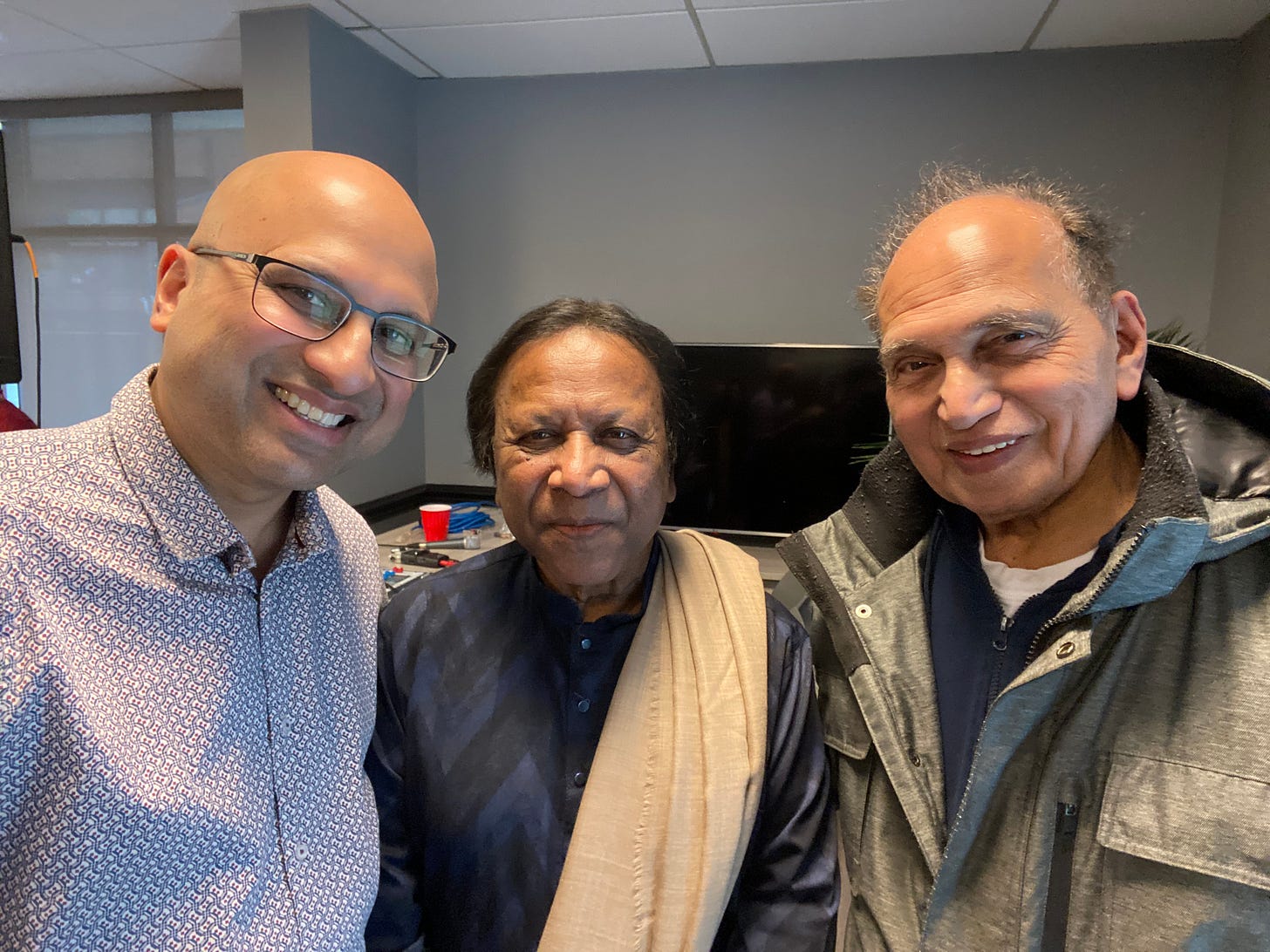

Over the last twenty-five years, I have been fortunate to hear Parvez perform live more than five times, and I’ve met him personally thrice. Our first encounter was at an initiation ceremony for one of his disciples in Toronto. The second one was backstage after a concert, where I tried to directly ask Parvez about the ways he uses space. He didn’t seem to understand what I was talking about and my mentioning postmodernism didn’t help either. There were at least fifteen others backstage, many of whom were more closely involved in the Hindustani music scene, competing for his interest that night too.

Parvez came back to Toronto last month and I saw him perform at the second of two events organized by Raga-Mala. This event was a baithak, an intimate session not unlike the living room-style events that are common in India, and thanks to one of Raga-Mala’s co-founders, my father Raya Bidaye, I was able to attend. A second round of thanks goes to Nimesh, one of Raga-Mala’s volunteers, who encouraged me to sit on the carpet, which gave me the privilege of sitting about 10 feet away from Parvez.

Once the baithak was over, a crowd formed around Parvez. I expected this, just as I expected almost no fans to gather around his tabla player, Amit Kavthekar, so my father and I introduced ourselves to him. Thanks to Dad, most of our conversation was in Marathi too.

As with any percussionist, a tabla player’s main purpose is to ensure a rhythmic foundation for the performance, but there are some who’ll try to steal the spotlight with gimmicky techniques at the expense of dialogue with their fellow musicians. Kavthekar is not that kind of tabla player. Instead, what I noticed was that he too emphasizes space, making him a perfect accompanist to Parvez. I brought this to his attention, and he agreed with my two-and-a-half-decade-long observations on Parvez’s sitar style.

Dad really wanted to greet Parvez, so we made our way over as the crowd thinned down. In those few minutes, I prepared myself to ask the same question I asked the last time I met him, but I suddenly also realized that I could rephrase the question by substituting “space” with “silence” – and it worked. We spoke with Parvez in English, and I said to him,

“Ustadji, I’ve been listening to you for twenty-five years, and I’ve always noticed that you emphasize silence in your playing.”

He bowed his head slightly and though a Muslim, he raised his hands up to offer a traditional Hindu namaskar. I know this is a common gesture among Hindustani musicians regardless of creed, but it’s also one I can’t help noting given the state of the world outside this bathaik.

Parvez then looked to me and said,

“A lot of people think that music is for entertainment, but I always say that it’s for bringing people to a place of soundlessness.

Because even between two notes there is music…”

I was about to ask him to elaborate further, but our conversation was cut by the arrival of a larger group of listeners. Which was fine. Parvez gave more than an answer; he gave me an affirmation. He also gave me a word, a concept – “soundlessness” – and I’m now holding it like a gift.

On the way home, Dad and I revisited this conversation, and we seem to have different interpretations of what kind of music lies “between those two notes.” I suspect, for Dad as well as for many trained musicians and knowledgeable listeners, Parvez’s words evoke shruti, that notion of “microtones,” like the frequencies between C and C#, through which South Asian vocalists glide so effortlessly. Shruti is also prized by some as the main characteristic that distinguishes all classical Hindustani and Carnatic music from other traditions. (Pop Shift makes a similar point through this Instagram-friendly explainer on Indian and Western music, defining what I call the glide as gamaka.)

For me, the once-miseducated postmodernist, the music that lies “between those notes” is a space of soundlessness, of audible and inaudible silences. This space is not absolute, nor is it static like a place, state, or destination. Rather, it’s a direction, possibly what Marshall McLuhan meant in at least the title to Through the Vanishing Point, which is what I hear whenever Parvez bends his strings to carry a note through the end of a melody and into silence.

Soundlessness is not unique to classical South Asian music, let alone to Parvez. What’s unique is his approach, his way of making his audience aware of it. This is not necessarily what puts him above Ravi Shankar or Vilayat Khan, but it does open up comparisons with my favourite works in minimalist jazz and techno – Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue and Plastikman’s Consumed.

Just as I was naïve to typecast Parvez as a postmodernist, I would be equally remiss to portray him here exclusively as a minimalist.

That afternoon at the baithak, Parvez opened with a solo sitar piece, building it up slowly to a fiery place:

The rock music listener in me wants to call this “shredding”, though it felt less like the speed metal of Megadeath and closer to the shoegazer indie-rock of Lush or Spacemen 3. Parvez was playing loud, his fingers were moving fast, but he was also creating a wall-of-sound effect. Yet, unlike the guitarists in the bands I’m mentally comparing him with, Parvez created this effect acoustically – no amplifiers, no pedals, no overdubs. Being able to sit so close to him, I could hear and see how it came from the total sound of his sitar strings, their frequencies vibrating off one another. I could also see that I had misunderstood sitar playing, not just from the postmodern angle, but once again in ways that relate to matters of space.

In the past, I assumed that the sitar was played like a guitar, where notes are produced by holding the string down in the spaces between the frets. Like most string players in the West, guitarists use one finger on the fretboard - one finger, one note. The proximity I had at the baithak allowed me to notice that Parvez often uses two fingers, one on each side of the fret. Sitar frets are metallic, but they are also thick, raised and curved. So, when the sitar player bends a string, they are also pressing down on the fret to bend the note. As a result, the fret is more than a just a visual marker for the note; it’s integral to the sitar player’s sound-generating process.

I will pause here, just in case I have misinterpreted this. Either way, I am ready for where this last observation will take me next.

(All photos and videos by Prasad Bidaye, except where indicated.)

An insightful piece, appreciated your nuanced storytelling.